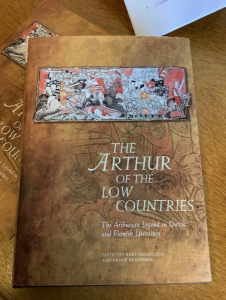

The well-known series of handbooks The Arthur of… was set up to replace the seminal Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages: A Collaborative History (ed. R.Sh. Loomis, 1959), better known as ALMA. The tenth and final volume closes off the series, published by the University of Wales Press. It is dedicated to the Arthurian Literature in Dutch and Flemish, the languages of the medieval Low Countries, and provides an overview of the historical and social context in which Middle Dutch Arthurian romances were created from the beginning of the thirteenth century onwards. There is an early fragment of a Tristan-story from the Rhine-Meuse region, but the main cradle was the multilingual county of Flanders. Quite a few French Arthurian romances originated in that county as well, as a separate chapter explains. Attention is paid to the manuscript tradition and the portrayal of Arthur in historical works. The three core chapters of the book reflect the development of the genre by first describing the translations of French verse romances, then the indigenous romances influenced by these translations and, finally, the translations of French prose romances. It is remarkable how popular the figure of Gauvain/Walewein was in the Low Countries; there even is an original Walewein-romance, describing his quest for a chessboard, a super sword and a lovely princess: Penninc and Pieter Vostaert’s Roman van Walewein. The most popular story, however, was that of Lancelot. The Old French Prose Lancelot was translated three, and probably even five, times into Middle Dutch, in verse translations as well as a prose version. In the 1320 Lancelot Compilation, a translation of the Lancelot–Queste del Saint Graal–Mort Artu was enriched by inserting seven Middle Dutch Arthurian romances into the larger narrative frame of the rise and fall of Lancelot, the Grail and King Arthur. And there is also a cycle of Merlin texts, based on the Old French Estoire de Merlin and Robert de Boron’s Joseph d’Arimathie and Merlin, and preserved in a Middle Low German rendition. The connections to German Arthurian material, sometimes based on Middle Dutch sources are discussed in a separate chapter, while an overview of modern Arthurian stories, plays, music, and games rounds off the book. It looks great, as the picture shows, and will be available for your perusal in the Reykjavík (2022) conference. Writing a review is also an option, just let me know (F.P.C.Brandsma@uu.nl)!