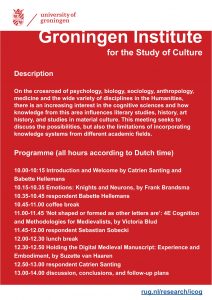

Project member Frank Brandsma will be presenting on ‘Emotions: Knights and Neurons’ at this exciting upcoming event:

Month: April 2021

Sif Ríkharðsdóttir speaks at the University of Gothenburg

The project PI, Professor Sif Ríkharðsdóttir, was invited to present at Göteborgs universitet (The University of Gothenburg) on 22 April, 2021. Her lecture, held online, addressed the medieval concept of pain and its various manifestations in Old Norse literature (titled ‘Pain, Love and the Embodiment of Emotion in Old Norse Literature’). Amongst other things, it considered the relationship between pain and ideological values, the physiological and psycho-somatic dimensions of pain and, ultimately, the function of pain as an emotion. In the lecture, Sif further suggested that pain in Old Norse literature is intimately interlinked with the notion of interior emotionality and its physical manifestation, i.e. the self – its emotive potentiality and its embodiment. Additional information about the lecture can be found here.

PI Sif Ríkharðsdóttir returns to the airwaves

Eco-Emotive Metaphor: Cultural Models for Emotions Workshop

On April 8th, the project’s Postdoctoral Researcher, Timothy Bourns, attended another workshop on medieval emotions: the Contributors Workshop for the volume Cultural Models for Emotions in the North Atlantic Vernaculars, 700-1400. The event was hosted by the University of Castilla La Mancha and will lead to a published volume with Brepols, edited by Professor Javier Díaz Vera, Dr Teodoro Manrique Antón, and Dr Edel Porter.

Timothy’s chapter is titled ‘Blood, Rain, and Tears: Eco-Emotive Metaphor in the Medieval North’. It examines the figurative relationship between emotion and the environment in Old Norse tradition, drawing on comparative material in Latin, English, Irish, and Saxon, with a focus on crying and fluids. These eco-emotive metaphors combine a somatic marker with an environmental feature, simultaneously revealing the depth and nature of an emotional gesture as well as the symbolic associations of various natural phenomena. The chapter will thus argue that the fluids of the living body and the natural environment form a figurative, affective, symbiotic relationship in the related emotive scripts of the medieval North.

Workshop II (St John’s College, Oxford)

On March 25th and 26th, we held our second Emotion and the Medieval Self in Northern Europe workshop, hosted by St John’s College, University of Oxford. This meeting was initially meant to take place in March 2020 and was then postponed to September 2020 and then again to March 2021. Finally, we held the workshop online, via Zoom, and it was immensely productive, energising, and successful!

On the first afternoon, Carolyne Larrington opened the workshop and led a round of general introductions, Sif Ríkharðsdóttir introduced and outlined the wider project, and Timothy Bourns discussed the project’s key terms and working definitions. Following a short break, we turned to the texts themselves; participants were asked to share a passage in advance which they then presented for group discussion. Textual discussions were divided into three sections: French, Celtic, and English (Norse, Dutch, and German were explored at our first workshop in Utrecht in November, 2019). In the opening French Session, we explored passages from Chrétien de Troyes’s Le Chevalier de la Charrette (introduced by Anatole Fuksas, Cassino and Southern Latium), the Carlisle fragment of Thomas d’Angleterre’s Le Roman de Tristan (Brindusa Grigoriu, Alexandru Ioan Cuza), and the non-cyclic Lancelot do Lac (Guillemette Bolens, Geneva). After a concluding discussion, we ended the afternoon with an afternoon social, featuring breakout rooms and a drink of choice!

We began the second day with the Celtic Session – romances in Irish, Scots, and Welsh. More specifically, we examined passages from Eachtra Uilliam (shared by Aisling Byrne, Reading), Hary’s The Wallace (Kate Ash-Irisarri, Bristol), and Ystoria Gereint uab Erbin, especially in conversation with Chrétien’s Erec et Enide (Natalia Petrovskaia, Utrecht). Following a concluding discussion of these passages, a break with breakout rooms, and a lunch break, we began the afternoon with the English Session: Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Wife of Bath’s Tale (Mary Flannery, Bern) and The King of Tars (Lucy Brookes, Oxford). After concluding our discussion of the English passages and another break with breakout rooms, we heard comments and feedback on the project and the workshop from Annette Volfing (Oxford) and had a fruitful concluding discussion about emotions and selfhood in medieval literature. We ended the day with another afternoon social, where we all decided to stay together in one room, where the good conversation and formation of new friendships continued.

We sincerely thank all of the participants for an incredibly instructive, engaging, and enjoyable workshop “in Oxford”, and we hope to stay in touch and see each other in person before long!

News from Frank Brandsma 2: Eat your heart out, Alice Cooper (adventures in editing)

Apart from participating in the Emotions and the Self project, I am also preparing a digital edition of a section of the Middle Dutch Lancelot compilation. Sometimes these two activities intersect. The episode that I am now editing is about Bohort’s experiences in the so-called Palace of Adventures in the Grail Castle. When Bohort visited the Grail Castle for the first time, he was spared a night in this dangerous place because of his pious attitude towards the Grail. Previously, Gawain, who had more eyes for the Grail maiden than for the Grail, was forced to spend the night in the Castle, suffered all kinds of abuse and disgrace, and was shamefully escorted out on a cart. Bohort has been admonished by a damsel some time ago that he really should have visited the palace and now is quite eager to experience its adventures. He finds a wonderful bed and is wounded by a lance that comes flying out of nowhere as he sits on the bed. Invisible hands take out the lance, but then Bohort has to fight a huge knight. When the fight goes Bohort’s way and he seems to have won, the wounded knight retires to an adjacent room and returns completely restored. Bohort resumes the fight, but now also takes care to keep the knight from entering the recovery room. He defeats his opponent and makes him promise to present himself at Arthur’s court. A colourful serpent then appears and fights a leopard. When the serpent is unable to win the fight, it draws back and the leopard disappears. From the mouth of the serpent a number of smaller serpents emerge. They begin to fight with their parent, until in the end all are dead. Bohort gets the strong impression that this all means something for the future (and it does, since the serpent stands for King Arthur who will in the Mort Artu section be attacked by his own kin while fighting Lancelot, the leopard).

And the night has only just begun. Next up is a very pale, greyish man with a precious harp. Two snakes that continuously bite him lie curled around his neck. He is lamenting and crying. The Alice Cooper look-a-like then tunes his harp and begins to sing a song about Joseph of Arimathea and his confrontation with a magician called Orphei about a magic castle on the Scottish moors. Afterwards, the harpist tells Bohort that only the knight who will sit in the Perilous Seat at the Round Table (that is: the Grail hero Galahad) will be able to end his suffering. Bohort might as well leave, such is the obvious message.

What strikes me in connection to emotions and the Self is what happens next. Bohort has been given this down-putting message and heard all kinds of wondrous things in the song, but what he asks the harpist is: How can you stand those biting snakes around your neck? Of all the things he could ask, this seems a minor detail and not very important for the story-line, yet his empathy works to create a sense of self for this young knight, I think. In our explanation of the term Self, we have said: “The constitution of medieval selfhood is premised on the reader’s (and the audience’s) projection of emotionality – and consequently of a presumed emotive interiority – onto the textual object.” That is exactly the case here, I think: Bohort becomes more of a self/person because he asks the most empathic, human question. The pale man then explains that he is being punished for the sin of pride and is actually glad to undergo this torment in his earthly life, because it may mean that he will not end up suffering eternally in hell. When he leaves the scene, he calls Bohort “lieve vrient” (“Dear friend”, l. 29.453), which is quite a different sentiment from his earlier put-offish attitude. Details like Bohort’s question are unobtrusive and easily overlooked when just reading the text, but editing, providing explanatory footnotes and translations brings them to the fore.

News from Frank Brandsma 1: New Handbook on Middle Dutch Arthuriana

The well-known series of handbooks The Arthur of… was set up to replace the seminal Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages: A Collaborative History (ed. R.Sh. Loomis, 1959), better known as ALMA. The tenth and final volume closes off the series, published by the University of Wales Press. It is dedicated to the Arthurian Literature in Dutch and Flemish, the languages of the medieval Low Countries, and provides an overview of the historical and social context in which Middle Dutch Arthurian romances were created from the beginning of the thirteenth century onwards. There is an early fragment of a Tristan-story from the Rhine-Meuse region, but the main cradle was the multilingual county of Flanders. Quite a few French Arthurian romances originated in that county as well, as a separate chapter explains. Attention is paid to the manuscript tradition and the portrayal of Arthur in historical works. The three core chapters of the book reflect the development of the genre by first describing the translations of French verse romances, then the indigenous romances influenced by these translations and, finally, the translations of French prose romances. It is remarkable how popular the figure of Gauvain/Walewein was in the Low Countries; there even is an original Walewein-romance, describing his quest for a chessboard, a super sword and a lovely princess: Penninc and Pieter Vostaert’s Roman van Walewein. The most popular story, however, was that of Lancelot. The Old French Prose Lancelot was translated three, and probably even five, times into Middle Dutch, in verse translations as well as a prose version. In the 1320 Lancelot Compilation, a translation of the Lancelot–Queste del Saint Graal–Mort Artu was enriched by inserting seven Middle Dutch Arthurian romances into the larger narrative frame of the rise and fall of Lancelot, the Grail and King Arthur. And there is also a cycle of Merlin texts, based on the Old French Estoire de Merlin and Robert de Boron’s Joseph d’Arimathie and Merlin, and preserved in a Middle Low German rendition. The connections to German Arthurian material, sometimes based on Middle Dutch sources are discussed in a separate chapter, while an overview of modern Arthurian stories, plays, music, and games rounds off the book. It looks great, as the picture shows, and will be available for your perusal in the Reykjavík (2022) conference. Writing a review is also an option, just let me know (F.P.C.Brandsma@uu.nl)!